Despite less overall volume loss than in MS and NMOSD, volumetric changes correlate with functional decline

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ffb277b0-0d3b-43b4-bcb9-fbd8de04616b/volumetric-mri-in-mogad-vs-other-demyelinating-diseases-1)

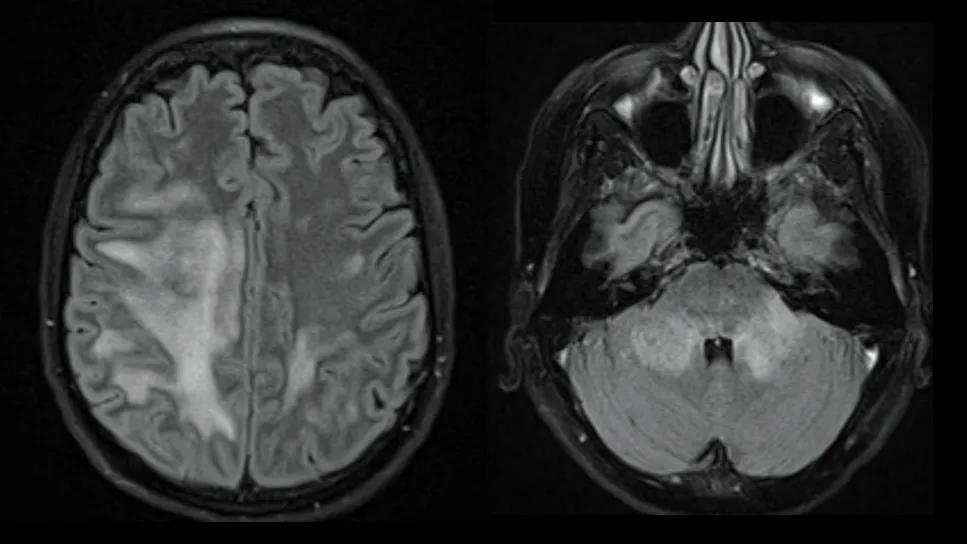

two brain MRIs side by side

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease (MOGAD) results in volume loss in all brain regions over time, with relative preservation of deep gray structures compared with multiple sclerosis (MS). Disability seen in MOGAD patients is associated with these volume losses.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

So concludes a new study by Cleveland Clinic researchers of longitudinal change on volumetric magnetic resonance imaging (vMRI) in MOGAD versus MS and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD). The findings were published in the Annals of Neurology.

“Little is known about brain volume loss in patients with MOGAD and how it might differ from what is seen with MS or NMOSD,” says senior author Amy Kunchok, MD, PhD, a neurologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Mellen Center for Multiple Sclerosis Treatment and Research.

She notes that although there are some cross-sectional studies of vMRI in MOGAD, there are few examining associations with disability or longitudinal volume. vMRI studies in MS have shown a correlation between regional atrophy and disability. “We undertook this study to better define the utility of vMRI in the clinical care of patients with MOGAD,” Dr. Kunchok explains.

The study’s cohort included participants from Cleveland Clinic databases for MOGAD, NMOSD and MS as well as healthy controls. Standardized vMRI metrics were compared between MOGAD patients and the other groups at baseline and over a three-year period.

MOGAD patients were matched 5:1 to MS participants by age, sex and disease duration; the NMOSD patients and healthy controls were included without matching. The 293-subject cohort broke down as follows: MOGAD (n = 32), MS (n = 160), NMOSD (n = 49) and healthy controls (n = 52). Median disease duration was 1.11 years in the MOGAD group versus 1.76 years in the MS group and 3.78 years in the NMOSD group.

Advertisement

vMRI with 3D fluid attenuation inversion recovery and 3D T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo was used to investigate longitudinal brain volume changes. Mixed linear models of time and group interactions were created to evaluate the potential impact of treatment on vMRI.

In tandem with the vMRI analysis, clinical disability metrics such as patient-determined disease steps and neuroperformance tests of manual dexterity, walking speed, contrast sensitivity and processing speed were evaluated.

At baseline, thalamic, caudate and putamen fractions were preserved in the MOGAD group compared with the MS group, with no differences between the MOGAD and NMOSD groups. Analysis of longitudinal changes in vMRI showed the following:

Overall, the volumetric changes in the MOGAD group, although less overall than in the comparator groups, correlated with clinical measures of disability. Specifically, upper cervical cord area was associated with patient-determined disease steps and contrast sensitivity. A significant association was found between lateral ventricle fraction and patient-determined disease steps, whereas whole brain fraction was associated with both patient-determined disease steps and processing speed.

Advertisement

“Deep gray matter was relatively preserved in MOGAD patients compared with the MS patients, whereas upper cervical cord area loss was greater in the patients with MS and NMOSD,” notes Dr. Kunchok. “Together, these findings demonstrate differences in the degree and distribution of volume loss that may reflect the differing pathophysiology of these disorders. Further, disability in MOGAD was associated with brain and upper cervical cord area volume loss, which suggests that these findings may be clinically relevant.”

This study has important clinical implications, as it suggests that people with MOGAD experience longitudinal regional volume loss compared with people without the disease, even though they initially may have normal-appearing brain MRIs with low lesion burden. The authors speculate that the tissue damage may not always be visible on standard MRI although it may be detectable with other advanced MRI techniques.

“Volumetric MRI gives us an objective way to track brain health in MOGAD,” Dr. Kunchok observes. “In clinical practice, it could provide a baseline at diagnosis and then be repeated over time to detect subtle change, monitor treatment effectiveness and help personalize care. While not yet routine at many centers due to availability and technical challenges, it has the potential to become a part of disease monitoring along with clinical assessments.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

It’s time to get familiar with this emerging demyelinating disorder

From dryness to diagnosis

Early experience with the agents confirms findings from clinical trials

Despite advancements, care for this rare autoimmune disease is too complex to go it alone

Treatment for scleroderma can sometimes cause esophageal symptoms

Patient’s symptoms included periorbital edema, fevers, weight loss

Could the virus have caused the condition or triggered previously undiagnosed disease?