New technology aids a Cleveland Clinic London patient with a complex arrhythmia

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4901582d-ddbd-43f5-945b-03850820c5ba/23-CCC-3852617-ULTC_Endo-ablation-transmitral-650x450-1_png)

23-CCC-3852617 ULTC_Endo ablation transmitral 650×450

The patient in the care of Cleveland Clinic London consultant cardiologist Magdi Saba, MB BCh, MSc, MD, posed a difficult challenge.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Symptomatically, “he was kind of reaching the end of his tether,” recalls Dr. Saba, who specializes in treating complex arrhythmias.

The 56-year-old man, diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy decades earlier, had recently developed ventricular tachycardia (VT) with bouts of cardiac syncope.

Despite increasingly aggressive antiarrhythmic therapy, he continued to experience shocks from his implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for recurrent VT. Subsequent radiofrequency (RF) ablation delivered epicardially and endocardially reduced, but did not eliminate, the arrhythmias and need for medication and periodic defibrillation.

The patient’s severely thickened left ventricular walls — 25 to 27 millimeters compared to the normal 10 mm — and the phrenic nerve’s close proximity to intended epicardial RF ablation targets had limited the procedure’s effectiveness. To avoid damaging the nerve, “we had to ablate cautiously and were not able to address all of the desirable targets,” Dr. Saba says. And RF energy’s inability to fully penetrate the thickened ventricular tissue and create deep lesions also hampered its efficacy.

The patient was withdrawn from amiodarone two months after the RF ablation but had to resume six weeks later following the return of VT and initiation of several ICD shocks. His anxiety increased.

“The VT was a lot more organized and a bit slower,” Dr. Saba says. “It seemed to be involving one circuit that we knew we needed to tackle. We needed something that would deliver deeper lesions than RF,” along with a way to overcome the phrenic nerve obstacle.

Advertisement

Dr. Saba’s innovative solution was to employ an ultra-low temperature cryoablation (ULTC) system — an emerging therapy for VT that creates deeper lesions endocardially — and to utilize a balloon catheter to lift the phrenic nerve from the heart’s surface, creating room for safe epicardial RF ablation.

The ULTC-RF combination was a first for Dr. Saba’s practice, and the first time in the United Kingdom that ULTC was used to treat VT.

“It’s new technology used safely in the right patient, with a good acute outcome,” he says. The patient “is feeling well and his arrhythmia is seemingly controlled. That’s a major step for Cleveland Clinic London and for the whole practice environment in the United Kingdom.”

Catheter ablation — initially using RF energy and later employing cryothermic energy — has been used for several decades as an interventional treatment for cardiac arrhythmias. Rapid heating or freezing of cardiac tissue causes cellular disruption and death and creates scarring that blocks or eliminates the source of aberrant electrical impulses.

Cryoablation has the advantage of freeze-mediated catheter adhesion to the target tissue, which stabilizes ablation of challenging areas and reduces collateral damage to nearby critical sites.

Previously, the physics of catheter cryoablation dictated the use of compressed gaseous nitrous oxide as the cryogenic agent. Nitrous oxide-charged catheters can achieve temperatures as cold as -89°C, which is adequate for ablation in some atrial regions but is insufficient to fully penetrate the depths of the thicker ventricular tissue.

Advertisement

Thus, RF energy has remained the predominant technology for VT ablations, but its lesioning penetration depth also is limited, sometimes requiring the use of bipolar or combined endo- and epicardially delivered ablations. VT recurrence rates following RF ablation range from 14% to 43% at one year.

Recently, a catheter cryoablation system that utilizes a more powerful, deeper-penetrating form of cryothermic energy has been developed. Adagio Medical’s vCLAS™ Ultra-Low Temperature Cryoablation System operates with near-critical nitrogen as its cryogenic agent. By maintaining nitrogen at the threshold between its gaseous and liquid state, the system can achieve catheter-tip temperatures approaching -196°C, providing rapid freezing and transmural myocardial lesions at depths up to 15 mm.

Outcomes of the first 13 patients with recurrent monomorphic VT treated with ULTC as part of the ongoing CryoCure-VT (Cryoablation for Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia) clinical trial were published in early 2023. The researchers reported that ULTC appeared to be effective in eliminating 95.2% of clinical VT in 90.9% of the patients while exhibiting a favorable safety profile.

Dr. Saba had read the initial CryoCure-VT results and believed the new technology could benefit his patient. The alternative would be to use bipolar RF ablation or cardiac stereotactic body radiotherapy, both of which would be challenging with a thickened ventricle and the adjacent phrenic nerve.

Dr. Saba contacted Adagio Medical, who was willing to provide access to the ULTC equipment on a compassionate-use basis since it has not yet received CE Mark medical device regulatory approval for general use in the European Economic Area. The UK Government’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency granted permission for exceptional use of the medical device in the patient’s case. Cleveland Clinic London’s Ethics Committee approved the technology’s use and the patient gave his consent.

Advertisement

Dr. Saba and his team performed the ULTC procedure in mid-March 2023 in Cleveland Clinic London’s electrophysiology lab, with the patient under general anesthesia.

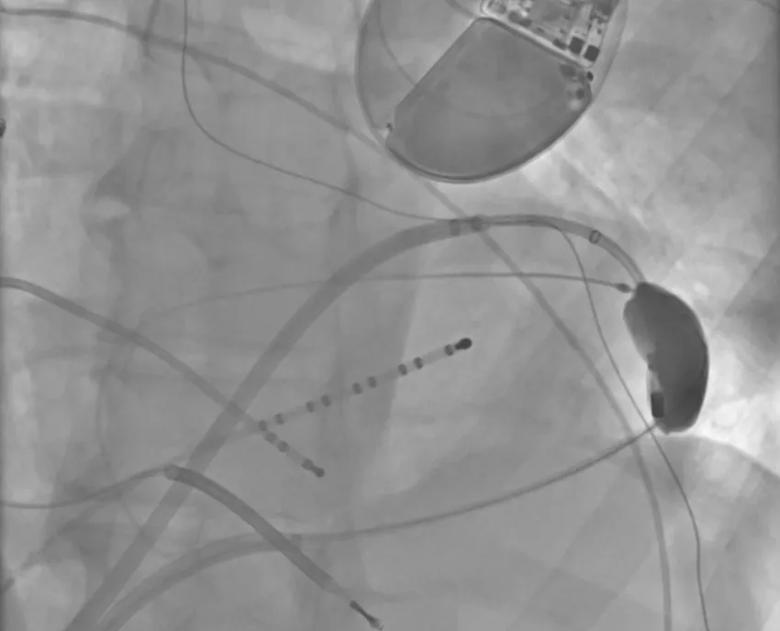

First, using femoral access and a trans-septal approach into the left atrium and a trans-mitral entry into the left ventricle, Dr. Saba advanced a mapping catheter to the ventricular apex. Voltage mapping confirmed the location of an apical scar. Ventricular stimulation induced VT. “We could never find very early signals endocardially,” Dr. Saba says, which indicated that the arrhythmia originated either in the mid-myocardium or epicardium.

The mapping catheter was exchanged for the ULTC catheter. The ULTC system consists of a control console and a deflectable, bidirectional catheter with electrode-equipped diagnostic and cryoablation elements for visualization and guidance, real-time electrogram recording and freezing/thawing. The control console delivers near-critical nitrogen along the 15-mm length of the catheter’s cryoablation element to form a large ice ball.

Dr. Saba created dual ULTC lesions in at least eight sites, each of three to five minutes’ duration, which achieved deep myocardial penetration and addressed the majority of the apical scar.

“We think we were reaching up to a 15 mm depth,” Dr. Saba says. The catheter’s stiffness and thickness restricted its maneuverability within the ventricle and prevented lesioning the full extent of the scar endocardially. When all accessible targets had been treated, it was still possible to induce a slower VT.

Advertisement

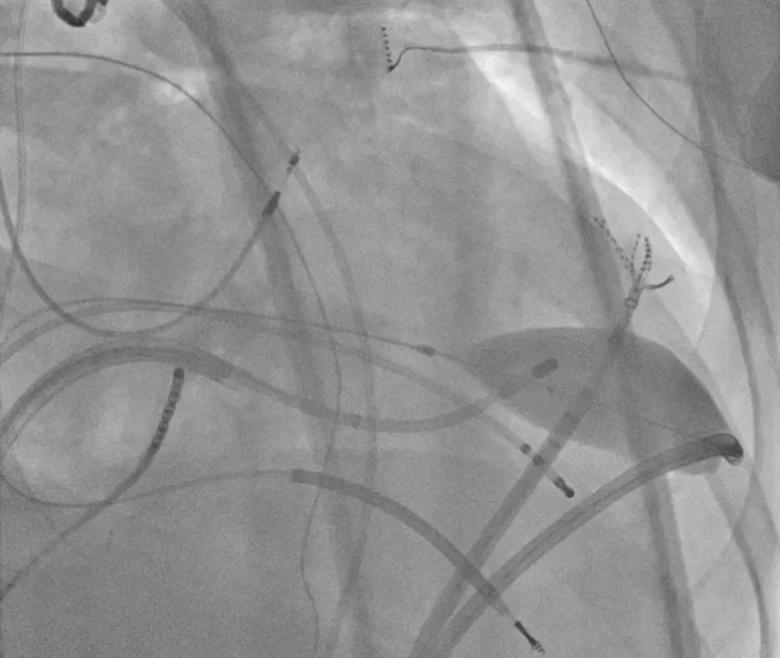

Dr. Saba knew he had to lesion the ventricle epicardially to have a chance at fully suppressing the arrhythmia. But ULTC wasn’t feasible there because of its potential to cryogenically damage nearby lung tissue and the phrenic nerve. The nerve also blocked access to the target area on the epicardium.

“We could only use RF energy, but we knew the phrenic nerve was sitting right there,” Dr. Sabo says. “So we had to be creative.”

Accessing the epicardium percutaneously through the chest wall, Dr. Saba and his team inserted two catheters — the RF ablation tool and a balloon catheter placed between the epicardial surface of the ventricle and the phrenic nerve. Inflating the balloon elevated the nerve away from the ablation target area, allowing safe delivery of RF energy.

“We were able to use that to ablate with radiofrequency where we wanted,” Dr. Saba says. “Then I went endocardial again, directly opposite the spot where the balloon had been sitting at the edge of the apical scar, and applied radiofrequency for several minutes there, hoping that the combination of ULTC plus RF would do the job.”

After the completed ablations, the team was no longer able to induce VT in the patient.

The procedure lasted nine hours.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c8395663-f577-411f-86a3-4e26d6f5a7b3/23-CCC-3852617-simultaneous-epi_endo-mapping-850x650-1_png)

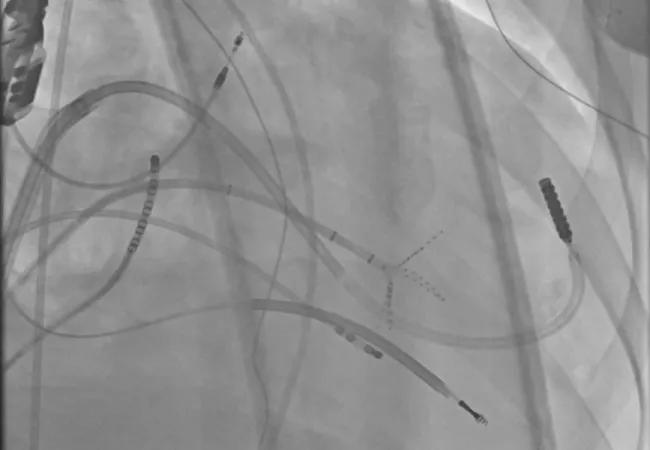

Simultaneous epicardial and endocardial mapping to locate the best ablation targets.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a5de7a32-ebd5-4533-bee5-729af019a527/23-CCC-3852617-ULTC_Endo-ablation-transaortic-850x650-1_png)

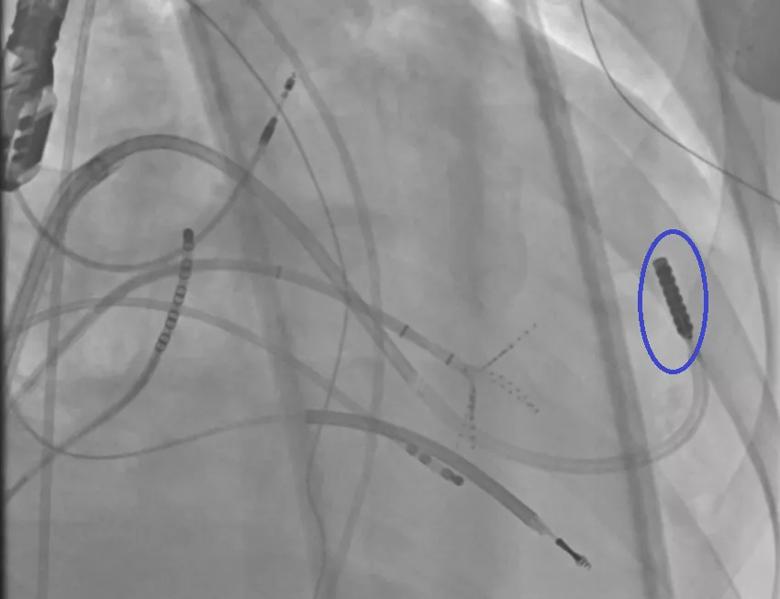

Endocardial ultra-low temperature cryoablation (ULTC) via the aortic valve. The ULTC catheter tip is circled in blue.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/23ba0938-67c1-4253-9593-448e0605a843/23-CCC-3852617-ULTC_Endo-ablation-transmitral-850x650-1_png)

Endocardial ULTC via the mitral valve. The ULTC catheter tip is circled in blue.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f019fa03-9b30-4d0c-b8f6-8793cfdc3be5/23-CCC-3852617-Balloon-protects-phrenic-850x650-1_png)

An epicardially positioned inflated balloon (right) protects the phrenic nerve while radiofrequency (RF) ablation is delivered epicardially.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a0548074-d2b7-4767-bcec-52df550fee41/23-CCC-3852617-endo-RF-oppo-epi-850x650-1_png)

RF ablation is delivered endocardially opposite the epicardial target, with the inflated balloon remaining in position.

For several days post-procedure the patient experienced some ventricular arrhythmia, a result of ablation-caused irritation and inflammation of the myocardium, Dr. Saba says. It was well-controlled with amiodarone and resolved within three weeks. Amiodarone was discontinued due to potential pulmonary complications. The patient has remained on mexiletine and a beta blocker. To date he has not experienced sustained VT requiring ICD discharge.

“If the critical ablation targets had been located in a more straightforward area, I would be a bit more confident in saying the arrhythmia’s source has been fully eliminated,” Dr. Saba says. “But when the ventricular walls are that thick, you cannot be certain.

“This patient is probably the most complex VT case to have been done in the UK in the past several years,” he says. “With the coverage of our whole team, the procedure went well. We achieved what we set out to achieve. He made a good recovery and went home.

“It’s a real success for private medicine in the UK to be able to access such new and novel technology quickly and apply it safely,” Dr. Saba says. “Our patient has really been helped by the presence of Cleveland Clinic London and its diligence in pushing things forward.”

Advertisement

Procedure allows for safer epicardial VT mapping and ablation

Study finds that in the absence of ACS, the yield is low and outcomes are unaffected

Further study needed to assess potential role in select subgroups

End-of-treatment VALOR-HCM analyses reassure on use in women, suggest disease-modifying potential

Cardiac imaging substudy is the latest paper originating from the VANISH trial

Vigilance for symptom emergence matters, a large 20-year analysis reveals

Phase 3 ODYSSEY-HCM trial of mavacamten leaves lingering questions about potential broader use

Our latest performance data in these areas plus HOCM and pericarditis