Our experts recap key changes and developments

By Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD; A. Marc Gillinov, MD; and Samir Kapadia, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) recently updated their joint guideline for managing patients with valvular heart disease. Published in December in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the 2020 guideline has added new advice for earlier timing of procedures, but the document is mostly conservative.

Nevertheless, there are notable new developments in this latest ACC/AHA guidance, including:

Below we summarize and reflect on a few of the most notable recommendations and changes in the portion of the guideline devoted to mitral valve disease. This complements a companion post we developed on the guideline’s discussion of aortic valve disease.

The new guideline emphasizes two general principles of great importance to those who treat patients with mitral valve disease:

Advertisement

Most mitral stenosis used to occur as a consequence of rheumatic disease. The criterion for severe mitral stenosis remains the same — namely, a mitral valve area ≤ 1.5 cm2. Intervention is indicated in symptomatic patients with severe mitral stenosis, with percutaneous mitral balloon commissurotomy (PMBC) recommended in those with suitable anatomy and less than moderate mitral regurgitation and surgery recommended in those who are not candidates for PMBC. In asymptomatic patients who develop pulmonary hypertension or atrial fibrillation (AF), intervention may also be considered.

The guideline does not address interventional treatment of AF in those with rheumatic mitral stenosis. Patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis who undergo surgical treatment of the valve should also receive surgical ablation of AF (i.e., maze procedure). The maze procedure will restore normal sinus rhythm in the majority of patients and excludes or removes the left atrial appendage, a major source of thrombi in those with AF.

The guideline employs the standard classification of mitral regurgitation (MR) as either primary or secondary. Primary MR refers to MR caused by disease of the valve apparatus, most commonly a result of degenerative disease in Western countries. Secondary MR is caused by changes in ventricular and/or atrial function and geometry. Treatment paradigms are distinct for those with primary and secondary MR.

Primary MR. In patients with severe primary MR caused by degenerative mitral valve disease, early surgical repair is strongly preferred. A normal left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in a patient with MR is > 60%. Therefore, an LVEF ≤ 60% represents the presence of LV dysfunction in the patient with severe MR. Given that the goal of surgery is to preserve LV function, patients with severe MR caused by degenerative disease should be referred for surgery before their LVEF declines below 60%. Similarly, patients should be referred for surgery before their LV end-systolic diameter exceeds 40 mm.

Advertisement

Most asymptomatic patients with severe MR caused by degenerative disease should undergo surgery before the development of even a hint of LV dysfunction. A strategy of “watchful waiting” can lead to irreversible LV dysfunction in patients with severe MR; return of normal LV function after surgery is not assured in patients with a preoperative LVEF below 60%. As in previous versions of the guideline, the onset of any symptoms is also an indication for surgery.

Mitral valve repair is preferred to mitral valve replacement in those with degenerative disease. Mitral valve repair is associated with an extraordinarily low operative mortality (< 1%, and < 0.1%at some centers, such as Cleveland Clinic) and with superior long-term survival relative to mitral valve replacement. The durability of mitral valve repair is excellent. The expectation for surgery in asymptomatic patients includes a repair rate exceeding 95% and an operative mortality below 1%; the guideline recommends referral of asymptomatic patients with severe MR to a Primary or Comprehensive Valve Center.

The guideline document does not address management of AF in those with degenerative mitral valve disease. Patients undergoing surgery for degenerative mitral valve disease who also have AF should receive a surgical maze procedure. Including management of the left atrial appendage, the surgical maze procedure restores normal sinus rhythm in approximately 80% of patients and reduces the long-term risk of thromboembolic complications. Adding the maze procedure to mitral valve repair does not increase operative risk.

Advertisement

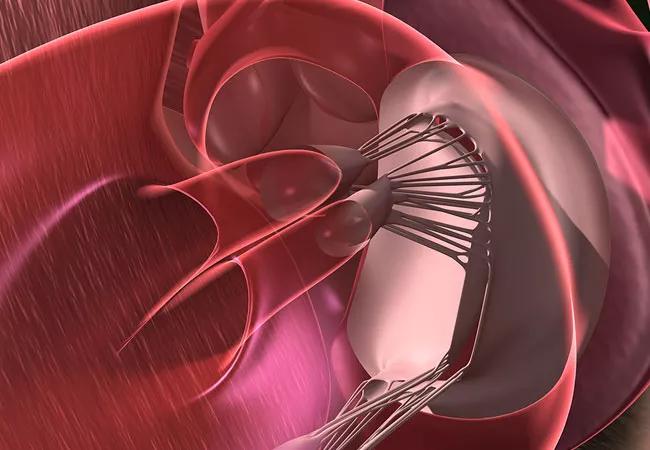

Additionally, the guideline specifies the role of transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) in patients with degenerative mitral valve disease. This therapy has been shown to be quite safe. However, because it does not manage MR as effectively as surgical repair, it is reserved for patients deemed to be at high or prohibitive risk for surgery. Future randomized trials may determine whether there is a role for this therapy in lower-risk patients.

Secondary MR. Secondary MR most commonly results from LV dysfunction but may also be caused by left atrial dilatation/dysfunction associated with AF, ischemic heart disease or cardiomyopathies. Thus, secondary MR is attributable to changes in cardiac structure and/or function rather than disease of the mitral valve. Criteria for severe secondary MR are the same as those used to grade primary MR — namely, effective regurgitant orifice ≥ 0.4 cm2 and regurgitant volume ≥ 60 mL.

In general, treatment of severe secondary MR begins with management of the underlying cardiac problem. In patients with LV dysfunction, this includes guideline-directed medical therapy, consideration of revascularization when appropriate and evaluation for cardiac resynchronization therapy in selected patients. Such treatments can diminish the severity of MR. Similarly, in patients with secondary MR associated with AF, restoration of sinus rhythm often results in a reduction of MR severity.

Surgery for severe secondary MR is appropriate in those who require concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting. Mitral valve repair by undersized annuloplasty is associated with suboptimal repair durability in such patients; therefore, chordal-sparing mitral valve replacement is preferred. The guideline briefly addresses surgical management of patients with severe secondary MR associated with AF. When such patients do not respond to standard attempts at restoration of sinus rhythm, surgical mitral valve repair with a concomitant maze procedure effectively manages both the MR and the AF.

Advertisement

Based on results of recent randomized trials, mitral TEER can be offered to highly selected patients with LV dysfunction who have severe symptoms and persistent secondary MR despite optimal guideline-directed medical therapy. Specific criteria for mitral TEER in such patients include LVEF of 20%-50%, LV end-diastolic diameter ≤ 70 mm and pulmonary artery systolic pressure ≤ 70 mmHg. Heart team evaluation for possible percutaneous or surgical options should be considered for patients who do not meet these criteria.

Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD: “The results of mitral valve repair, both initial and long-term, have matured, hence the recommendation for earlier intervention in this latest guideline. Indeed, we have not had a death from mitral valve repair since 2014, including over 2,000 patients who have undergone robot-assisted mitral valve repair. While we use mitral TEER, this is limited to high-risk patients for now. Newer transcatheter technologies have been slower to mature for the mitral valve but hold promise for the particular challenge of severe mitral valve annular calcification.”

Marc Gillinov, MD: “In patients with mitral valve prolapse, valve repair is preferable to valve replacement, and our mitral valve repair rate is nearly 100%. In addition, the majority of patients with isolated mitral valve prolapse can be offered a robotic approach, our least invasive operation for mitral valve repair.”

Samir Kapadia, MD: “The COAPT study provided scientific evidence that treatment of secondary MR decreases mortality and hospitalizations in patients with heart failure, as highlighted in this guideline. Management of secondary MR requires a multidisciplinary approach involving multiple cardiology subspecialties, including heart failure, electrophysiology, interventional and imaging. Surgical management also requires specialized teams with expertise in advanced heart failure management. We have passionate leaders involved in taking care of these patients in each of these specialties, both to provide the best care to our patients and to advance the field with innovations.”

Dr. Svensson is Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Sydell and Arnold Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. Dr. Gillinov is Chair of the Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Dr. Kapadia is Chair of the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine.

Advertisement

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients