Large cohort study finds significant effect in men and nonsmokers

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d82f718f-5305-403a-a50e-26a9a0bc5c48/23-HVI-4400491-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

23-HVI-4400491 CQD 650×450

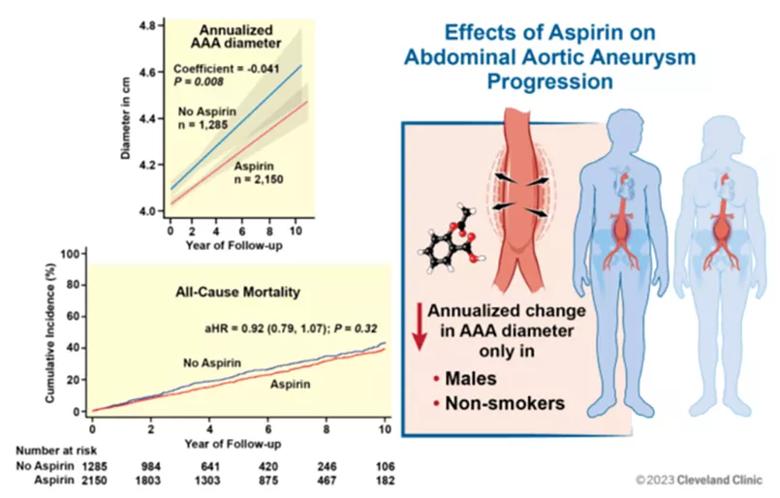

Low-dose daily aspirin appears to slow the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs), particularly in men and nonsmokers. So finds a retrospective study conducted at Cleveland Clinic (JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6[12]:e2347296) involving the largest cohort at a single institution analyzed on this issue, including more than 3,000 adults followed over a period of up to 10 years. Survival rates were similar in patients who did and did not take aspirin, with no increased risk of major bleeding in aspirin takers and no change in aneurysm dissection or rupture.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Our findings indicate that daily low-dose aspirin slows the advancement of abdominal aortic aneurysms,” says the study’s corresponding author, Scott Cameron, MD, PhD, Section Head of Vascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic. “No other medication has been found to have a comparable effect.”

Cleveland Clinic researchers have been active in investigating the protective role of antiplatelet therapy for AAAs. A letter in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2020;75[13]:1609-1610) detailed an analysis of nearly 1.5 million patients with AAA identified from the U.S. National Inpatient Sample and determined that antiplatelet agents were associated with significantly lower incidence of AAA, along with protection from dissection and rupture in patients with an existing AAA. The use of anticoagulants did not show these trends, except for a marginal protective effect against rupture.

Dr. Cameron has also conducted preclinical research on the effects of antiplatelet agents on human tissue and murine models of AAA, as described in the Journal of Clinical Investigation (2022:132[9]:e152373) and summarized in a Consult QD article. The research implicated olfactory receptors in regulating platelet activation and aneurysmal progression, potentially offering new targets for therapy.

Without data from large clinical trials establishing the use of aspirin in AAA management, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines gave low-dose aspirin (75-162 mg daily) a Class 2b indication for managing AAA — indicating a weak recommendation — in their 2022 updated guideline for AAA diagnosis and management. Cleveland Clinic staff were involved in creating the guideline, which was published in Circulation (2022;146[24]:e334-e482).

Advertisement

The current study on the effects of daily low-dose aspirin on AAAs was designed to provide evidence from real-world clinical data to inform guidelines.

The cohort was identified from patients who underwent AAA ultrasound screening and at least one additional abdominal vascular ultrasound at Cleveland Clinic between 2010 and 2020. Adults with AAA (defined as maximal aortic diameter ≥ 3.0 cm below the renal arteries) were included; those with a history of prior aneurysm repair, dissection or rupture were excluded.

Data from 3,435 patients were analyzed, including 2,150 (63%) verified to be on aspirin therapy, with the majority taking 81 mg and over a median duration of 10.6 years. Overall, average age was 73 years, 78% were males, 89% were white and median follow-up was 4.9 years (interquartile range, 2.5-7.5 years).

Major outcomes comparing patients taking aspirin versus those not taking aspirin were as follows:

These effects were seen only in men and nonsmokers. “This means that male patients who continue to smoke will lose the protective effect of aspirin,” Dr. Cameron notes.

Overall, no difference between aspirin users and nonaspirin users was detected in rates of all-cause mortality, major bleeding, or a composite of aneurysm dissection, rupture or repair at 10 years. The graphic below summarizes several key outcomes.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2b52c871-8a62-4d2a-bc02-bea2a2db0d03/23-HVI-4400491-CQD-Inset_jpg)

Dr. Cameron concludes that this large, long-term study provides strong evidence that aspirin can help reduce aneurysm progression. He notes that the study raises some interesting questions:

Dr. Cameron adds that a randomized clinical trial is warranted to better determine the role of aspirin for managing aneurysmal disease, but he speculates that this may be prohibitively difficult, given that it would likely take decades to see an effect.

In the meantime, Dr. Cameron routinely puts his AAA patients on maintenance low-dose aspirin, with the justification of the updated ACC/AHA guidelines and with the understanding that most patients have AAA as a consequence of atherosclerosis, so he considers aspirin therapy to be secondary prevention. “It is an inexpensive, low-risk medication that over time may potentially stave off a rupture, dissection or the need for intervention due to enlargement,” he says.

Advertisement

“This study was an extension of previous elegant mechanistic studies performed by Dr. Cameron’s team that implicated a causal contribution of platelets to AAA development — a perfect example of going from bedside to bench and back again to the bedside,” says Stanley Hazen, MD, PhD, Co-Section Head of Preventive Cardiology at Cleveland Clinic and a co-author on the manuscript.

At the same time, further investigation of this question would be welcome, notes Sean Lyden, MD, Chair of Vascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “It would be ideal to confirm that aspirin still confers its effects at larger aneurysm sizes, so prospective data are needed to validate these results,” he says.

Dr. Cameron acknowledges the contributions of the study’s first author, Essa Hariri, MD, who served as Cleveland Clinic Chief Medical Resident when the study was conducted.

Advertisement

Advertisement

New Cleveland Clinic data challenge traditional size thresholds for surgical intervention

Study finds comparable midterm safety outcomes, suggesting anatomy and surgeon preference should drive choice

New review distills insights and best practices from a high-volume center

Blood test can identify patients who need more frequent monitoring or earlier surgery to prevent dissection or rupture

Recent Cleveland Clinic experience reveals hundreds of cases with anatomic constraints to FEVAR

Multicenter pivotal study may lead to first endovascular treatment for the ascending aorta

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Impacts include major emphases on multidisciplinary teams, shared decision-making